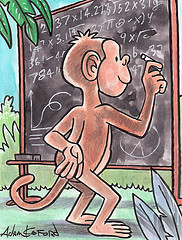

I’m terrible at math. And by terrible, I mean that Albert Einstein could totally out-math me, and he’s been dead for fifty-five years*.

Several weeks ago, I was planning a dinner for myself, Leigh, and my mother. I wanted to make three 1/3 lb. burgers, and I found myself flummoxed at how to calculate the amount of ground beef I needed. I texted my friend Tank, and he replied with a single line of text: “Is this a trick?”

Last week, a student corrected me on my math in the middle of a lecture. I had asked the students to complete an exercise wherein they needed to find argumentative claims in a particular set of readings. I asked them to find three definitional claims, three causal claims, three resemblance claims, and three evaluation claims. As I was finishing up my lecture, I told them, “After you’ve found your nine claims,” and as soon as I said that, a student yelled out “Twelve. Three and three and three and three make twelve.”

I doubt I could identify a causal chain of events that would explain why I’m an utter math failure. It’s more realistic to say that there were probably many different variables in the equation that equals me being a math-dummy. Granted, I have had some truly atrocious math teachers. My first math class in high school was taught by a coach, and he obviously wished to be anywhere but in a room with a group of degenerates teaching math. He let us completely run wild. We would cheat on tests right in front of him, and he never said a word. Our classroom was on the second floor, and one day, while our “teacher” was in the room, we wrote “BITCH” in big, bold letters on a sheet of notebook paper, and then we tied that piece of notebook paper to a long string. We then lowered it down to the window of the classroom below us, so that the much reviled Spanish teacher would know exactly what we thought of her.

With the benefit of hindsight, combined with my experience of actually teaching, I feel pretty confident that my former teachers weren’t the whole problem. No, my biggest problem was that in grammar school, I was smart enough that I didn’t really need to work to make good grades. I got straight “A”s without ever having to open a book. Thus, I never actually learned the basics of mathematics because I never had to learn them.

And now I find myself asking for help on problems as simple as 1/3 + 1/3 + 1/3.

As a young student, nothing bugged me quite as much as having a teacher tell me to “show your work.” I heard that all the time. Show your work. Show your work. I hated hearing that because I didn’t understand why I needed to go through the trouble of writing out every step in a long division problem if I already knew the answer. I always felt that “show your work” was just a way to keep the students busy or a way to combat against cheating.

This is a small digression, but one that I think is important. As an undergraduate at Baylor, I became highly active with the karate club, and my participation in the karate club remains one of the few fond memories I have of Baylor. It probably helps that I met my wife in the there, but also, the experiences I had with the club are still informing my outlook on life.

One of the many things that James Melton, my late karate instructor, taught me was that a student doesn’t ever truly understand a particular thing until he or she is able to teach that thing to another student. I might be able execute a particular move well, but until I can explain how I execute that move I probably don’t understand it as well as I could.

I ran up against this little pedagogical peccadillo when I began teaching writing. I found that while I knew what a grammatical sentence looked like, I didn’t know how to explain why it was grammatical. This is why that many ESL students perform quite well in grammar classes and why native speaking students will oftentimes perform poorly in them. An ESL student has probably learned English by memorizing grammatical/mechanical constructions and verb conjugation, while the native speaker just speaks without actually understanding how his or her language actually works.

Now, as a math student, I either wasn’t taught why I needed to show my work, or I never understood the principle. Students don’t need to show their work to prove they haven’t been cheating, although that is certainly a valid, if not Big Brothery, reason. No, the students need to be able to show their work so that they understand the material. A student will never truly know something until they’re able to successfully teach that thing to another person, and having students show their work provides them with a way to “teach” the material without having to actually talk to another person.

*In the spirit of full disclosure, I’m willing to admit that I had to use the calculator to subtract 1955 from 2010.

Bahaha

I never fought math… I just viewed it as little puzzles that unlocked other things my brain to comprehend that were not math related.

But I’m crazy.

** Things that were and were not math related.

I absolutely need that shirt. 😀

Warren, I never had to fight math. It was clear math would win, so I always backed down.