I’m about three-quarters of the way through Joseph J. Ellis’s Pulitzer Prize-winning book Founding Brothers, and it occurred to me this morning that  the political and ideological divide between John Adams and Thomas Jefferson is one that, as a country, we’re still struggling to overcome. For those of you that may have forgotten your American history, Adams was a Federalist, and as such, he believed that the country needed a strong, central government because he was convinced that the republican values that precipitated the revolution would likely lead to a dissolution of the newly formed, and highly volatile, United States. Jefferson, on the other hand, was a Democratic-Republican, and he firmly believed in self-government, which, consequently, meant that he viewed a strong, centralized government as tantamount to tyranny.

the political and ideological divide between John Adams and Thomas Jefferson is one that, as a country, we’re still struggling to overcome. For those of you that may have forgotten your American history, Adams was a Federalist, and as such, he believed that the country needed a strong, central government because he was convinced that the republican values that precipitated the revolution would likely lead to a dissolution of the newly formed, and highly volatile, United States. Jefferson, on the other hand, was a Democratic-Republican, and he firmly believed in self-government, which, consequently, meant that he viewed a strong, centralized government as tantamount to tyranny.

Ellis describes the two thus:

They were an incongruous pair, but everyone seemed to argue that history had made them into a pair. The incongruities lept out for all to see: Adams, the short, stout, candid-to-a-fault New Englander; Jefferson, the tall, slender, elegantly elusive Virginian; Adams, the highly combustible, ever combative, mile-a-minute talker, whose favorite form of conversation was an argument; Jefferson, the always cool and self-contained enigma, show regarded debate and argument as violations of the natural harmonies he heard inside his own head…[t]hey were the odd couple of the American Revolution. (163)

To some degree, the United States is still haunted by the ghosts of Adams’s and Jefferson’s political disagreements. A direct comparison of the Federalists to the Democrats and the Democratic-Republicans to present day Republicans would, of course, be ludicrous. For one thing, the political ideologies of Adams and Jefferson were inextricably entwined with the Revolution. As often as Americans whinge and bitch about politics, Adams and Jefferson actually lived through political turmoil. For another, Jefferson hated religion, and this is not something that has remained unnoticed among current Republicans. Ellis claims that “like Voltaire, Jefferson longed for the day when the last king would be strangled with the entrails of the last priest” (139). While Adams wasn’t as venomous towards religion, his father was a minister and he considered himself a Unitarian, he most certainly held beliefs that current reading would view as deistic. Their deistic beliefs alone make a direct comparison with modern-day politics futile.

But I think I can easily provide an analogy of the political divide between Adams and Jefferson while simultaneously providing one that will help us understand the schism between political parties today:

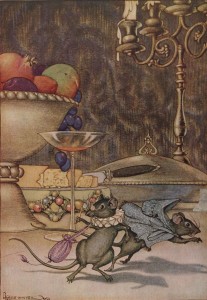

“The Town Mouse and the Country Mouse” by Aesop.

Now you must know that a town mouse once upon a time went on a visit to his cousin in the country. He was rough and ready, this cousin, but he loved his town friend and made him heartily welcome. Beans and bacon, cheese and bread, were all he had to offer, but he offered them freely. The town mouse rather turned up his long nose at this country fare, and said, “I cannot understand, cousin, how you can put up with such poor food as this, but of course you cannot expect anything better in the country; come you with me and I will show you how to live. When you have been in town a week you will wonder how you could ever have stood a country life.” No sooner said than done: The two mice set off for the town and arrived at the town mouse’s residence late at night.

“You will want some refreshment after our long journey,” said the polite town mouse, and took his friend into the grand dining room. There they found the remains of a fine feast, and soon the two mice were eating up jellies and cakes and all that was nice. Suddenly they heard growling and barking.

“What is that?” said the country mouse.

“It is only the dogs of the house,” answered the other.

“Only,” said the country mouse, “I do not like that music at my dinner!” Just at that moment the door flew open; in came two huge mastiffs; and the two mice had to scamper down and run off.

“Good-bye, cousin,” said the country mouse.

“What! Going so soon?” said the other.

“Yes,” he replied. “Better beans and bacon in peace than cakes and ale in fear.”

Okay, I’m sure most of you have heard this fable before. And while I don’t necessarily agree with the moral it’s supposed to impart, it does capture the animosity between present day Democrats and Republicans and Adams and Jefferson. Jefferson made no apologies about being a Francophile, and he certainly did his fair share of traveling and living abroad, but he would immediately retire to his farm at Monticello at the drop of a hat, and in his heart he felt as if he was a simple, gentlemanly Virginian farmer. Of course, he wasn’t. He was much more than that, but what’s important here is not reality but self-identification. Jefferson viewed himself as a simple country mouse. Adams, on the other hand, was born and lived near Boston and educated at Harvard. He spent a good part of his life living in the hustle-bustle of cities like Boston, Philadelphia, London, and New York. Unlike Jefferson, Adams didn’t long a particular place or location to engage in silent contemplation. Adams did long for the company of his wife Abigail, but he seemed happiest in crowded cities where he could argue and discuss whatever was on his mind. He was the quintessential town mouse.

Many republicans still view the world through country mouse eyes. To a country mouse, self-government makes sense. You know all your mousey neighbors and they all know you. There’s no need for a strong government to help enforce laws because all the mice know each other. Taxes don’t make sense because the little country mouse village has no need for a government, much less an adequately-funded government. Unions don’t make sense to a country mouse because you know your boss. If there’s a problem, just go talk to the head mouse in charge. You know him, he knows you, and you probably know each other’s families. Obviously you can come to some agreement if you talk it out.

But to a town mouse, the country mouse’s view of the world is untenable. There’s so much going on in the town that self-government would never work. There are out-of-control mastiffs–someone has to do something about that. There’s great food and drink, but the company that makes jelly is based in another country, and the mice that work in the local factory aren’t getting a fair shake. Long hours, no benefits, and abusive bosses. The mousey employees had complained to their bosses, but they didn’t have any real power (rumors were the plant was owned by a group of felines from overseas). The mice thought about looking for other work, but the cake factory was the same. So they had to form a union so that their grievances were heard.

It’s no secret that urban voters traditionally vote democrat and rural voters vote republican. And if you’ve lived in both places it’s not hard to see why. When you live in the country you tend to feel, similarly to Jefferson and the country mouse, that you can take care of yourself. Since you aren’t forced to contend with many different kinds of people that hold many differing views on society, you feel disconnected from the rest of the world, and the need of a strong government seems tyrannical. But when you live in the town, like Adams and the town mouse, you realize that self-government simply isn’t enough. There are far too many out of control dogs running around for people to deal with. And beyond that, there are so many conflicting views, such as politics and religion, that without a strong government to continually pursue a common goal, the citizenry would be dissolute and combative.

In my experience, which is obviously anecdotal, people who live in the country oftentimes have a distorted view of city life. They view it as much more violent than it actually is, and they tend to view foreigners much more suspiciously. They also view most poverty as the result of laziness, which of course, it most definitely is not. They also have frighteningly skewed outlooks on unions, and they see any taxes as an imposition bordering on tyranny.

Of course, Aesop’s fable is fairly pro-country mouse, but like Adams, I think that dogmatic adherence to either of the philosophies of Jeffersonian self-government or Hamiltonian Federalism is pure folly, and the only way for the country to flourish is to find a way to continue to combine those two seemingly antagonistic philosophies.

Besides, beans and bacon can get boring as hell. I’d risk a fight with a bull mastiff for a shot at some jellies and cake now and then. I feel like Adams would support me on this.

Post Script: For more of my thoughts on country life, click here.

Post-Post Script: I’ll make a formal announcement at the end of the week, but I want to restart the reading group. Anniina suggested the sequel to Oryx and Crake, The Year of the Flood. I want to give those people that haven’t read Oryx and Crake the time to read it. Again, I’ll post details later this week.